SIMD (Single Instruction, multiple data)

- Allows us to process 16 (or more) bytes or more with one instruction

- Supported on all modern CPUs (phone, laptop)

- Data-parallel types (SIMD) (recently added to C++26)

Not All Processors are Equal

| processor | year | arithmetic logic units | SIMD units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apple M* | 2019 | 6+ | |

| Intel Lion Cove | 2024 | 6 | |

| AMD Zen 5 | 2024 | 6 |

SIMD Support in simdjson

- x64: SSSE3 (128-bit), AVX-2 (256-bit), AVX-512 (512-bit)

- ARM NEON

- POWER (PPC64)

- Loongson: LSX (128-bit) and LASX (256-bit)

- RISC-V: upcoming

simdjson: Design

- First scan identifies the structural characters, start of all strings at about 10 GB/s using SIMD instructions.

- Validates Unicode at 30 GB/s.

- Rest of parsing relies on the generated index.

- Allows fast skipping. (Only parse what we need)

- Can minify JSON at 10 to 20 GB/s

Usage

You are probably using simdjson:

- Node.js, Electron,...

- ClickHouse

- WatermelonDB, Apache Doris, Meta Velox, Milvus, QuestDB, StarRocks

The Problem

Imagine you're building a game server that needs to persist player data.

You start simple:

struct Player {

std::string username;

int level;

double health;

std::vector<std::string> inventory;

};

The Traditional Approach: Manual Serialization

Without reflection, you may write this tedious code:

// Serialization - converting Player to JSON

fmt::format(

"{{"

"\"username\":\"{}\","

"\"level\":{},"

"\"health\":{},"

"\"inventory\":{}"

"}}",

escape_json(p.username),

p.level,

std::isfinite(p.health) ? p.health : -1.0,

p.inventory| std::views::transform(escape_json)

);

Manual Deserialization (simdjson)

object obj = json.get_object();

p.username = obj["username"].get_string();

p.level = obj["level"].get_int64();

p.health = obj["health"].get_double();

array arr = obj["inventory"].get_array();

for (auto item : arr) {

p.inventory.emplace_back(item.get_string());

}

When Your Game Grows...

struct Equipment {

std::string name;

int damage; int durability;

};

struct Achievement {

std::string title; std::string description; bool unlocked;

std::chrono::system_clock::time_point unlock_time;

};

struct Player {

std::string username;

int level; double health;

std::vector<std::string> inventory;

std::map<std::string, Equipment> equipped; // New!

std::vector<Achievement> achievements; // New!

std::optional<std::string> guild_name; // New!

};

Happy programmer...

The Pain Points

This manual approach has several problems:

- Maintenance Nightmare: Add a new field? Update both functions!

- Error-Prone: Typos in field names, forgotten fields, type mismatches

Our goal: Seamless Serialization/Deserialization

How do other languages do it?

C#

string jsonString = JsonSerializer.Serialize(player, options);

Player deserializedPlayer = JsonSerializer.Deserialize<Player>(jsonInput, options);

How can C# Implementation be so Elegant?

It is using reflection to access the attributes of a struct during runtime.

Rust (serde)

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize)] // Annotation is required

pub struct player {}

// Rust with serde

let json_str = serde_json::to_string(&player)?;

let player: Player = serde_json::from_str(&json_str)?;

Rust Reflection

- Rust does not have any built-in reflection capabilities.

- Serde relies on annotation and macros.

Reflection as Accessing the Attributes of a Structure

| language | runtime reflection | compile-time reflection |

|---|---|---|

| C++ 26 |  |

|

| Go |  |

|

| Java |  |

|

| C# |  |

|

| Rust |  |

(macros) (macros) |

Now it's our Turn to Have Reflection!

With C++26 reflection and simdjson, all that boilerplate disappears:

// Just define your struct - no extra code needed!

struct Player {

std::string username;

int level;

double health;

std::vector<std::string> inventory;

std::map<std::string, Equipment> equipped;

std::vector<Achievement> achievements;

std::optional<std::string> guild_name;

};

Automatic Serialization

// Serialization - one line!

void save_player(const Player& p) {

std::string json = simdjson::to_json(p); // That's it!

// Save json to file...

}

Automatic Deserialization

// Deserialization - one line!

Player load_player(std::string& json_str) {

return simdjson::from(json_str); // That's it!

}

Runnable example at https://godbolt.org/z/Efr7bK9jn

Benefits of our implementation

- No manual field mapping

- Minimal maintenance burden

- Handles nested and user-defined structures and containers automatically

- You can still customize things if and when you want to

What Happens Behind the Scenes

// What you write:

Player p = simdjson::from(runtime_json_string);

// What reflection generates at COMPILE TIME (conceptually):

Player deserialize_Player(const json& j) {

Player p;

p.username = j["username"].get<std::string>();

p.level = j["level"].get<int>();

p.health = j["health"].get<double>();

p.inventory = j["inventory"].get<std::vector<std::string>>();

// ... etc for all members

return p;

}

The Actual Reflection Magic

// Simplified snippet, members stores information about the class

// obtained via std::define_static_array(std::meta::nonstatic_data_members_of(^^T, ...))...

ondemand::object obj;

template for (constexpr auto member : members) {

// These are compile-time constants

constexpr std::string_view field_name = std::meta::identifier_of(member);

constexpr auto member_type = std::meta::type_of(member);

// This generates code for each member

obj[field_name].get(out.[:member:]);

}

See full implementation on GitHub

Compile-Time vs Runtime: What Happens When

struct Player {

std::string username; // ← Compile-time: reflection sees this

int level; // ← Compile-time: reflection sees this

double health; // ← Compile-time: reflection sees this

};

// COMPILE TIME: Reflection reads Player's structure and generates:

// - Code to read "username" as string

// - Code to read "level" as int

// - Code to read "health" as double

// RUNTIME: The generated code processes actual JSON data

std::string json = R"({"username":"Alice","level":42,"health":100.0})";

Player p = simdjson::from(json);

// Runtime values flow through compile-time generated code

Try out this example at https://godbolt.org/z/WWGjhnjWW

struct Meeting {

std::string title;

long long start_time;

std::vector<std::string> attendees;

std::optional<std::string> location;

bool is_recurring;

};

// Automatically serializable/deserializable!

std::string json = simdjson::to_json(Meeting{

.title = "CppCon Planning",

.start_time = std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::milliseconds>(

std::chrono::system_clock::now().time_since_epoch()

).count(),

.attendees = {"Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"},

.location = "Denver",

.is_recurring = true

});

Meeting m = simdjson::from(json);

The Container Challenge

We can say that serializing/parsing the basic types and custom classes/structs is pretty much effortless.

How do we automatically serialize ALL these different containers?

std::vector<T>,std::list<T>,std::deque<T>std::map<K,V>,std::unordered_map<K,V>std::set<T>,std::array<T,N>- Custom containers from libraries

- Future containers not yet invented

The Naive Approach

// The OLD way - repetitive and error-prone!  void serialize(string_builder& b, const std::vector<T>& v) { /* ... */ }

void serialize(string_builder& b, const std::list<T>& v) { /* ... */ }

void serialize(string_builder& b, const std::deque<T>& v) { /* ... */ }

void serialize(string_builder& b, const std::set<T>& v) { /* ... */ }

// ... 20+ more overloads for each container type!

void serialize(string_builder& b, const std::vector<T>& v) { /* ... */ }

void serialize(string_builder& b, const std::list<T>& v) { /* ... */ }

void serialize(string_builder& b, const std::deque<T>& v) { /* ... */ }

void serialize(string_builder& b, const std::set<T>& v) { /* ... */ }

// ... 20+ more overloads for each container type!

Problem: New container type? Write more boilerplate!

The Solution: Concepts as Pattern Matching

Concepts let us say: "If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck..."

template <typename T>

concept container =

requires(T a) {

{ a.size() } -> std::convertible_to<std::size_t>;

{

a[std::declval<std::size_t>()]

}; // check if elements are accessible for the subscript operator

};

- Could also use iterators (

begin()).

Containers, but not string types

template <typename T>

concept container_but_not_string =

requires(T a) {

{ a.size() } -> std::convertible_to<std::size_t>;

{

a[std::declval<std::size_t>()]

}; // check if elements are accessible for the subscript operator

} && !std::is_same_v<T, std::string> &&

!std::is_same_v<T, std::string_view> && !std::is_same_v<T, const char *>;

Serialize 'array-like' Containers

template <class T>

requires(container_but_not_string<T>)

constexpr void atom(string_builder &b, const T &t) {

if (t.size() == 0) {

b.append_raw("[]");

return;

}

b.append('[');

atom(b, t[0]);

for (size_t i = 1; i < t.size(); ++i) {

b.append(',');

atom(b, t[i]);

}

b.append(']');

}

vector, array, deque, custom containers...

For Deserialization

- Many ways to add values to a container

push_back,append,emplace_back

template <typename T>

concept appendable_containers =

(details::supports_emplace_back<T> || details::supports_emplace<T> ||

details::supports_push_back<T> || details::supports_push<T> ||

details::supports_add<T> || details::supports_append<T> ||

details::supports_insert<T>);

Write a Helper Function

template <appendable_containers T, typename... Args>

constexpr decltype(auto) emplace_one(T &vec, Args &&...args) {

if constexpr (details::supports_emplace_back<T>) {

return vec.emplace_back(std::forward<Args>(args)...);

} else if constexpr (details::supports_emplace<T>) {

return vec.emplace(std::forward<Args>(args)...);

} else if constexpr (details::supports_push_back<T>) {

return vec.push_back(std::forward<Args>(args)...);

} else if constexpr (details::supports_push<T>) {

return vec.push(std::forward<Args>(args)...);

} else if constexpr (details::supports_add<T>) {

return vec.add(std::forward<Args>(args)...);

} else if constexpr (details::supports_append<T>) {

return vec.append(std::forward<Args>(args)...);

} else if constexpr (details::supports_insert<T>) {

return vec.insert(std::forward<Args>(args)...);

// ....

Deserialize 'array-like' Containers

auto arr = json.get_array()

for (auto v : arr) {

concepts::emplace_one(out, v.get<value_type>());

}

Concepts + Reflection = Automatic Support

When you write:

struct GameData {

std::vector<int> scores; // Array-like → [1,2,3]

std::map<string, Player> players; // Map-like → {"Alice": {...}}

MyCustomContainer<Item> items; // Your container → Just works!

};

The magic:

- Reflection discovers your struct's fields

- Concepts match container behavior to serialization strategy

- Result: MOST containers work automatically - standard, custom, or future!

Write once, works everywhere™

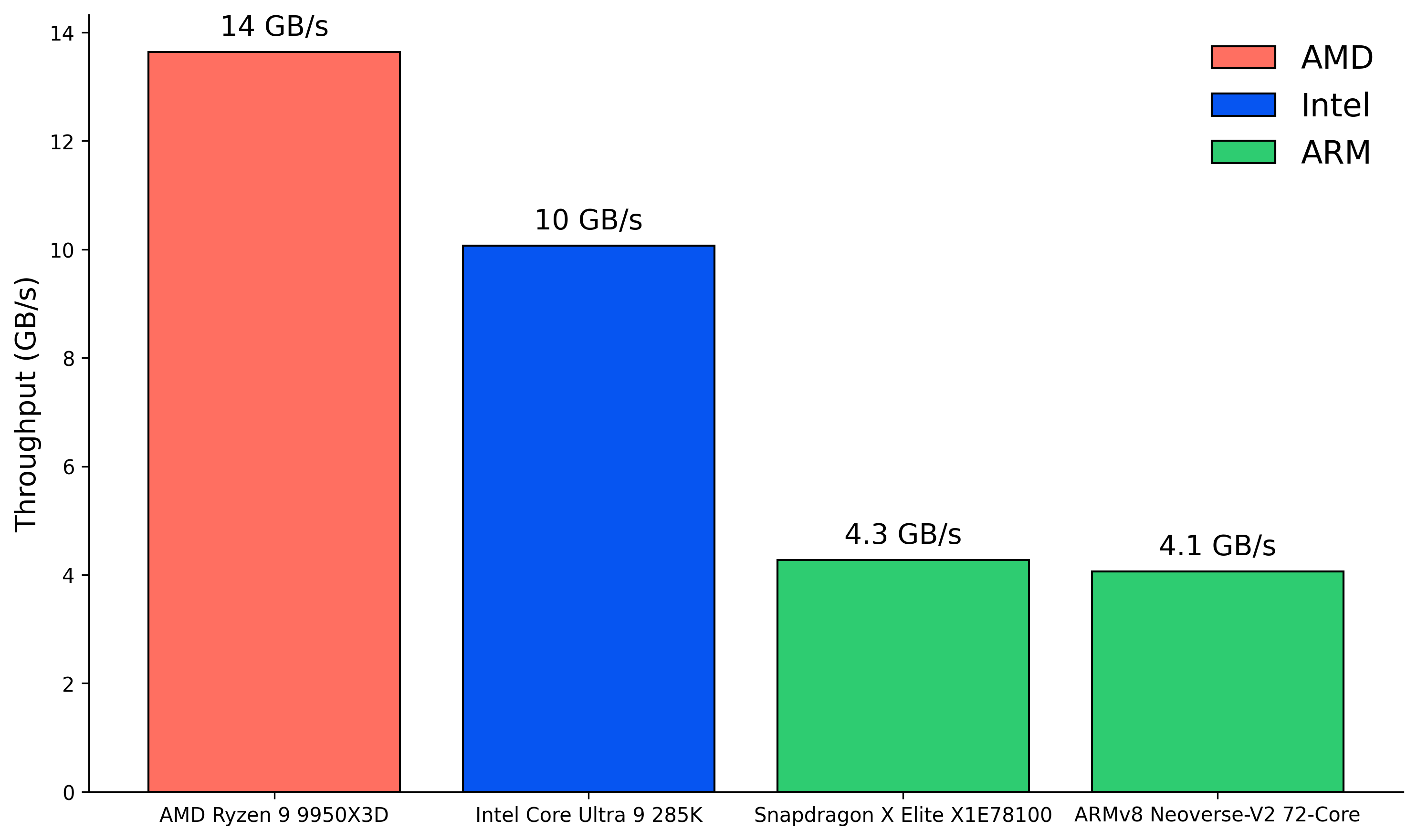

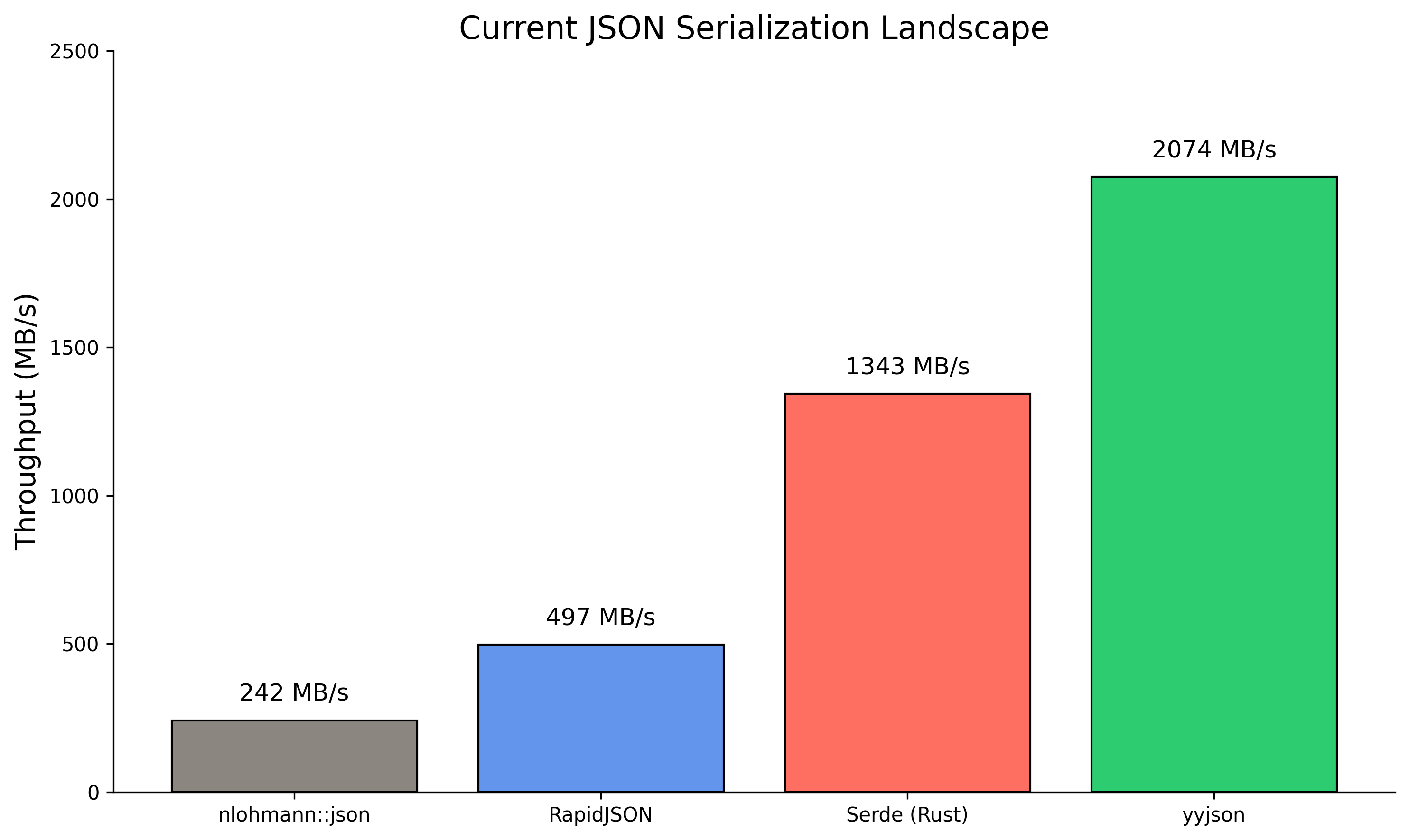

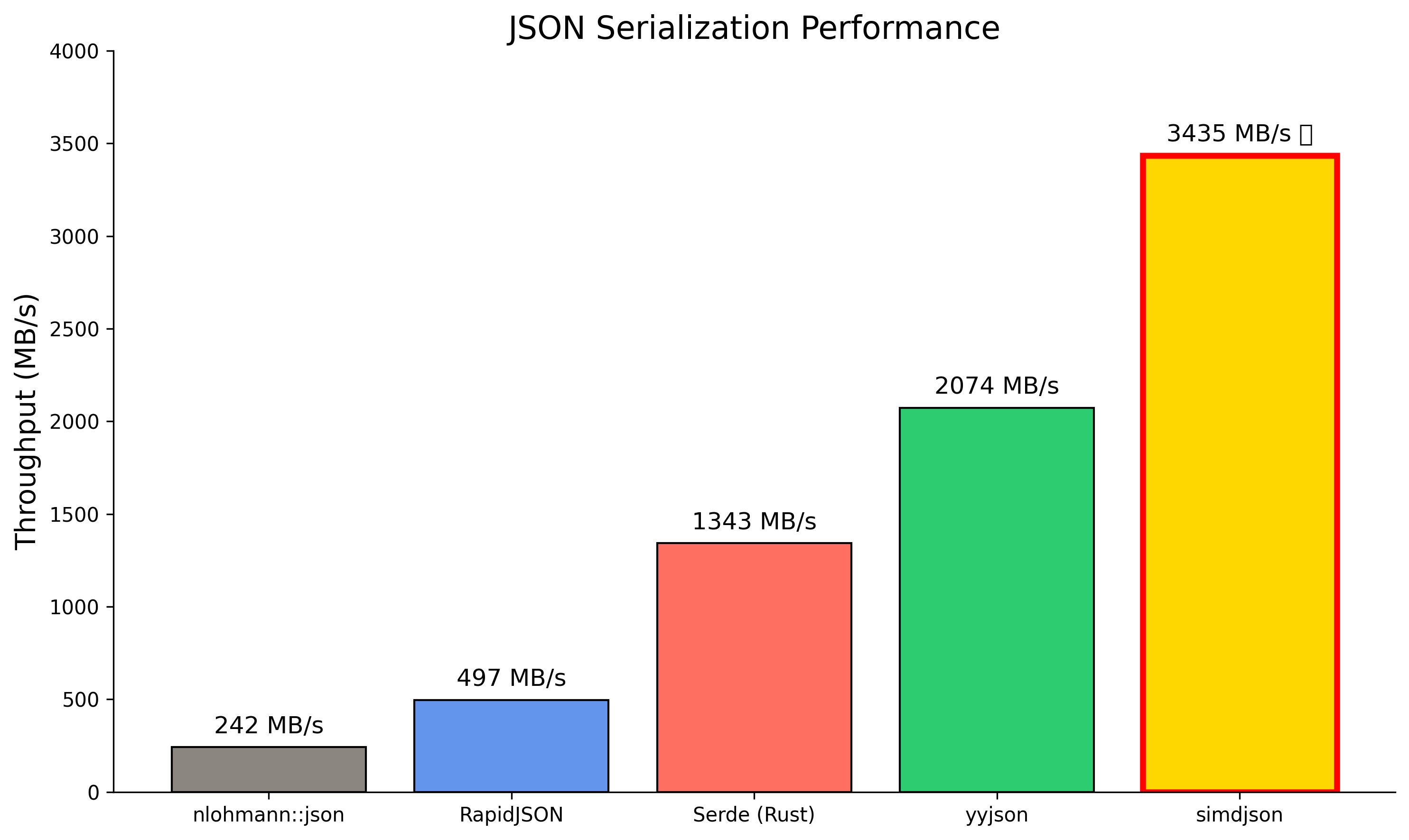

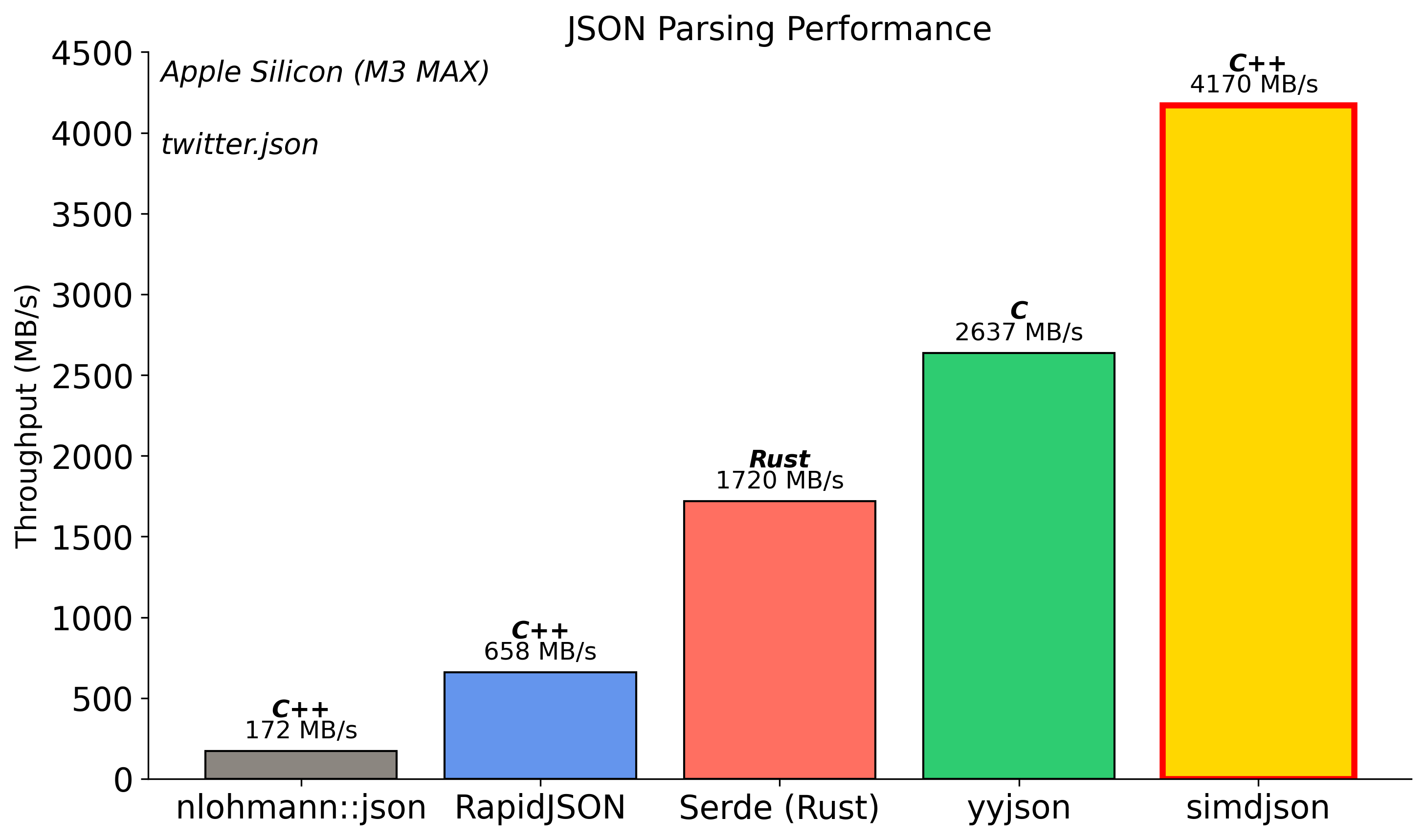

How fast are we?

3.6 GB/s - 14x faster than nlohmann, 2.1x faster than Serde!

Serialization Ablation Study

How We Achieved 3.6 GB/s

What is Ablation?

From neuroscience: systematically remove parts to understand function

Our Approach (Apple Silicon M3 MAX):

- Baseline: All optimizations enabled (3,600 MB/s)

- Disable one optimization at a time

- Measure performance impact

- Calculate contribution:

(Baseline - Disabled) / Disabled

Three Key Optimizations

- Consteval: Compile-time field name processing

- SIMD String Escaping: Vectorized character checks

- Fast Integer Serialization: Optimized number handling

Combined Performance Impact

| Optimization | Twitter Contribution | CITM Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Consteval | +100% (2.00x) | +141% (2.41x) |

| SIMD Escaping | +42% (1.42x) | +4% (1.04x) |

| Fast Digits | +6% (1.06x) | +34% (1.34x) |

Optimization #1: Consteval

The Power of Compile-Time

The Insight: JSON field names are known at compile time!

Traditional (Runtime):

// Every serialization call:

write_string("\"username\""); // Quote & escape at runtime

write_string("\"level\""); // Quote & escape again!

With Consteval (Compile-Time):

constexpr auto username_key = "\"username\":"; // Pre-computed!

b.append_literal(username_key); // Just memcpy!

Optimization #2: SIMD String Escaping

The Problem: JSON requires escaping ", \, and control chars

Traditional (1 byte at a time):

for (char c : str) {

if (c == '"' || c == '\\' || c < 0x20)

return true;

}

SIMD (16 bytes at once):

auto chunk = load_16_bytes(str);

auto needs_escape = check_all_conditions_parallel(chunk);

if (!needs_escape)

return false; // Fast path!

Optimization #3: Fast Integer serialization

- Use the equivalent of

std::to_chars - Could use SIMD if we wanted to

- "Converting integers to decimal strings faster with AVX-512," in Daniel Lemire's blog, March 28, 2022, https://lemire.me/blog/2022/03/28/converting-integers-to-decimal-strings-faster-with-avx-512/.

- Replace fast digit count by naive approach based on

std::to_stringstd::to_string(value).length(); - Only 34% worse in one dataset.

What about compilation time?

We've observed a 6% slow-down when compiling simdjson with static reflection enabled. (clang p2996 experimental branch).

Learning Curve

error: invalid use of incomplete type 'std::reflect::member_info<

std::reflect::get_public_data_members_t<Person>[0]>'

in instantiation of function template specialization

'get_member_name<Person, 0>' requested here

note: in instantiation of function template specialization

'serialize_impl<Person>' requested here

note: while substituting template arguments for class template

Key Technical Insights

-

With reflection and concepts, code is shorter and more general

-

Fast compile time

-

Compile-Time optimizations can be awesome

-

SIMD: String operations benefit

-

Many optimizations may help

Thank You!

C++ Reflection Paper Authors

- The authors of P2996 for making compile-time reflection a reality

Compiler Implementation Teams

- Everyone that implemented P2996 and made it publicly available.

- Early adopters testing and providing feedback

Compiler Explorer Team

- Matt Godbolt and contributors

simdjson Community

- All contributors and users (John Keiser, Geoff Langdale, Paul Dreik...)

Questions?

Daniel Lemire and Francisco Geiman Thiesen

GitHub: github.com/simdjson/simdjson

Thank you!